6 Common Reasons Your Thyroid Symptoms Fluctuate

It's common for thyroid patients to feel frustrated when symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, hair loss, weight changes, mood swings, joint pain, or temperature intolerance seem to come and go, worsen, or shift without clear reason.

From a functional medicine/root cause perspective, fluctuating symptoms are often a sign that the body is dynamically responding to underlying imbalances — not just a static "thyroid problem."

Functional medicine views the thyroid as part of an interconnected system (hormones, immune system, gut, adrenals, detoxification pathways, and more), and symptoms change because these root causes are rarely fixed in one state.

6 common reasons your thyroid symptoms fluctuate:

1. Autoimmune Flares (Especially in Hashimoto's or Graves')

In autoimmune thyroid conditions like Hashimoto's thyroiditis (the leading cause of hypothyroidism) or Graves' disease (hyperthyroidism), the immune system mistakenly attacks the thyroid gland. This isn't a constant attack but occurs in waves or "flares."

In Hashimoto's, antibodies such as thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAb) and thyroglobulin antibodies (TgAb) target key thyroid enzymes and proteins. During a flare, Th1 or Th17 immune pathways activate, leading to inflammation and thyroid cell destruction. This can cause an unpredictable and inconsistent release of stored thyroid hormones giving you temporary hyperthyroid-like symptoms such as anxiety or palpitations before swinging back to more hypothyroid symptoms as tissue is lost from the destruction.

Some common triggers for this happening are: Stress which elevates cortisol causing a shift in immune system balance, viral or bacterial infections which cause issues via molecular mimicry— Epstein-Barr virus along with gluten proteins resemble thyroid tissue, seasonal changes, poor sleep, or inflammatory foods.

Molecular mimicry causes your immune system to attack your thyroid.

Why symptoms change: Flares can last days to weeks, with antibody levels spiking and dropping, creating unpredictable symptom intensity.

What to do about it: Test antibody levels repeatedly because they do fluctuate-it’s nice to have a baseline level you can measure against, identify food triggers with an elimination diet or at a minimum a gluten-free diet trial, support immune regulation with low-dose naltrexone (LDN) under supervision if everything else you have tried isn’t helping, anti-inflammatory herbs like turmeric, or addressing infections

2. Impaired T4-to-T3 Conversion

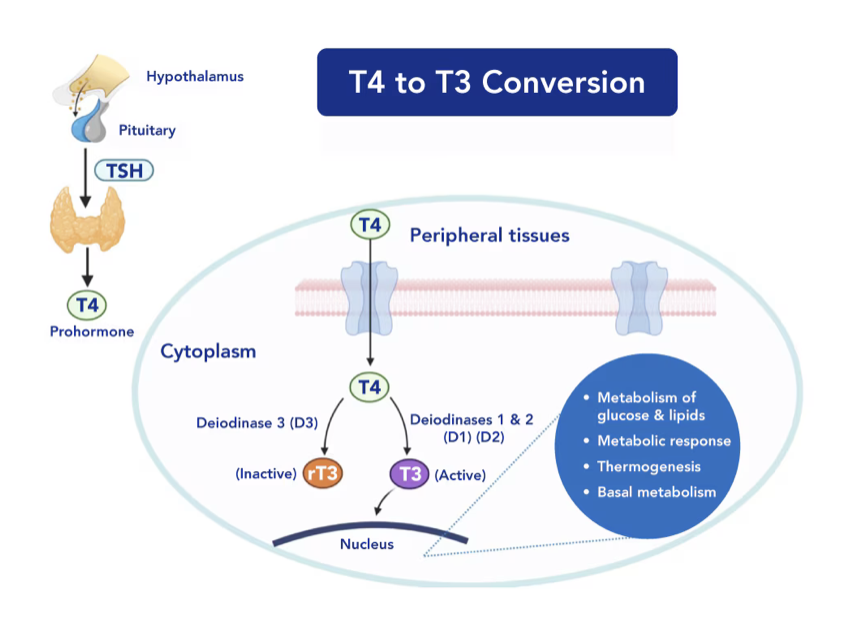

Levothyroxine (Synthroid) provides mostly inactive T4, which the body must convert to active T3 via deiodinase enzymes. This process is highly variable and inefficient in many thyroid patients.

There are three deiodinases—D1 and D2 activate T4 to T3 (in liver, kidneys, muscles, and gut), while D3 inactivates to reverse T3 (rT3), which blocks T3 receptors. Stress, inflammation, or deficiencies shift toward more rT3 production. Having muscle- meaning lifting weights to gain muscle and having a healthy gut can improve thyroid hormone conversion.

Why it fluctuates: Conversion depends on daily factors like calorie intake. You need to make sure you are eating enough because low-calorie diets impair conversion. Inflammation levels, liver function, and even time of day also affect conversion. Poor conversion means you might have "normal" labs but you still feel hypothyroid.

Key influencers: High cortisol or cytokines (from stress/infection) inhibit D1/D2; fasting or illness reduces it further. Take note of the health “experts” online telling you ladies to fast. If you have thyroid problems, fasting is the last thing you should be doing.

Conversion of T4 to T3 depends on many things including diet, liver health, and inflammation.

Root cause approach: Test free T3, free T4, and reverse T3 (optimal ratio >20). Optimize with selenium, zinc, and avoiding extreme dieting. Some benefit from adding T3 medication (like liothyronine or desiccated thyroid) if conversion remains poor. Test your mineral levels before supplementing.

3. Adrenal and Stress Axis Dysregulation

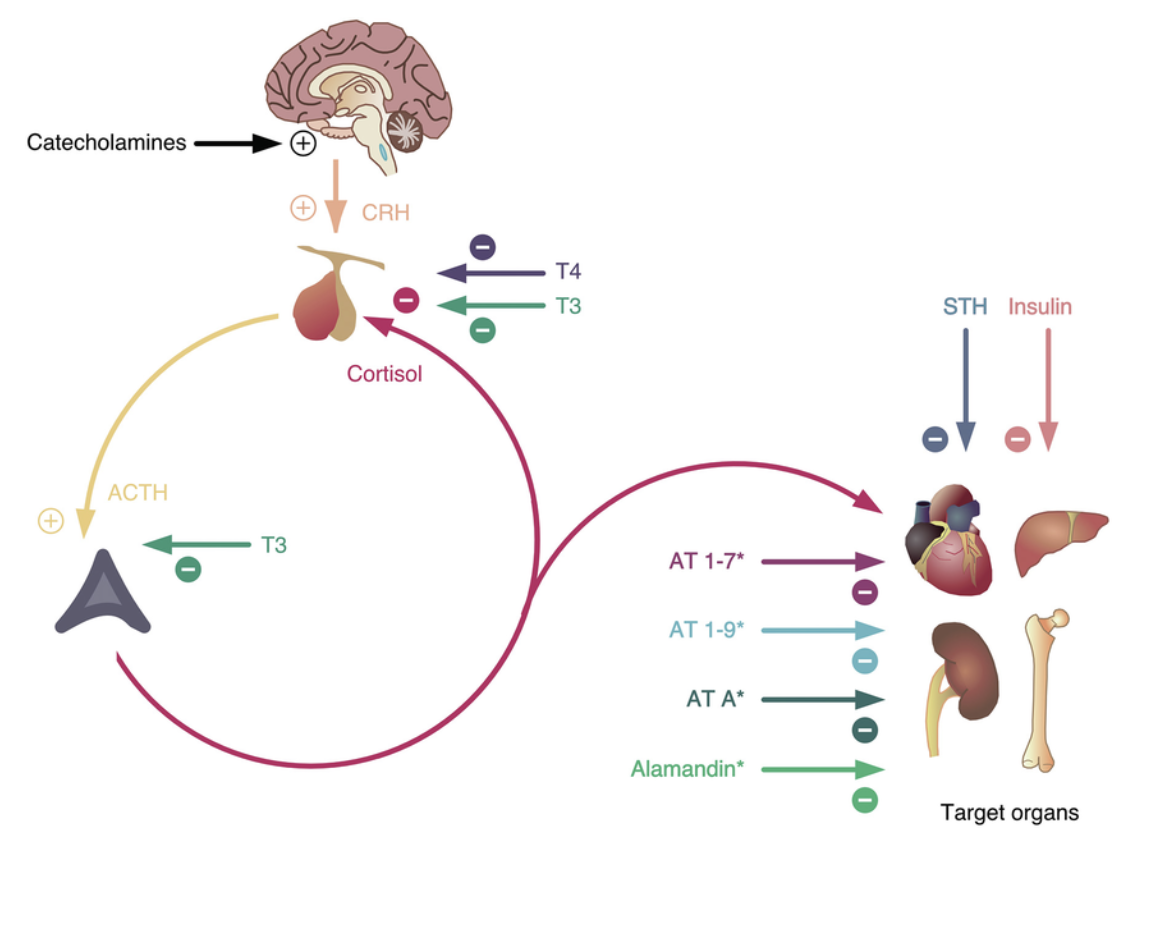

The thyroid and adrenals are tightly linked via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body's stress response system.

Chronic stress signals the hypothalamus to release CRH, prompting pituitary ACTH and adrenal cortisol. Elevated cortisol suppresses TSH production, blocks T4-to-T3 conversion, and increases rT3. In later stages ("adrenal fatigue"), cortisol can drop too low, worsening fatigue and hormone signaling.

Stress is a big factor in adrenal and thyroid function.

Why symptoms fluctuate: Stress isn't constant—daily life (work, relationships, poor sleep) causes cortisol spikes or crashes, directly altering thyroid function hour-to-hour or day-to-day.

Common patterns: Worse symptoms in the morning (cortisol should peak) or during high-stress periods.

Root Cause approach: 4-point salivary or urine cortisol testing to map patterns. Support with adaptogens (ashwagandha, rhodiola), phosphorylated serine for high cortisol, B vitamins, magnesium, and stress reduction practices (breathwork, boundaries).

4. Gut and Microbiome Imbalances

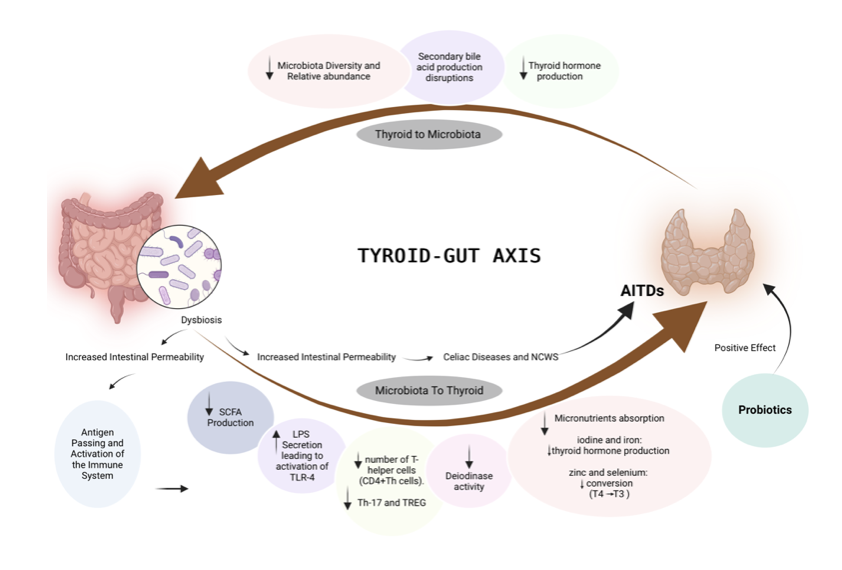

The gut is a major site of thyroid hormone activation and absorption, often called the "thyroid-gut axis."

About 20% of T4-to-T3 conversion occurs in the intestines via bacterial enzymes (e.g., sulfatases). Dysbiosis (imbalanced bacteria), SIBO, or leaky gut impairs this, reduces medication absorption, and allows toxins (LPS) to enter bloodstream, fueling systemic inflammation and autoimmunity.

Triggers for fluctuation: Dietary changes, antibiotics, infections, or stress alter the microbiome rapidly, shifting symptoms after meals or bowel changes.

dietary changes and infections rank among the most common and potent triggers for fluctuating thyroid symptoms, particularly in autoimmune cases like Hashimoto's. They often explain why symptoms can feel worse on certain days or after specific events, even when medication doses stay stable.

What you eat directly influences gut integrity, microbiome composition, inflammation levels, blood sugar stability, and immune tolerance. Changes—whether introducing trigger foods or removing them—can cause short-term shifts in thyroid function and symptoms

Inflammatory or Trigger Foods: Certain foods provoke immune responses or increase systemic inflammation, especially in sensitive individuals. Gluten stands out as a top offender due to molecular mimicry—its protein structure (gliadin) closely resembles thyroid tissue (thyroperoxidase enzyme). When the immune system attacks gluten, it can cross-react and attack the thyroid, spiking antibodies and causing a flare.

Other common triggers include dairy (casein mimicry), soy, eggs, nightshades, or grains. Processed foods high in sugar or refined carbs drive inflammation via advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and disrupt the microbiome.

Blood Sugar Swings: High-glycemic meals (sugary or carb-heavy) cause insulin spikes followed by crashes, triggering cortisol release. Cortisol then suppresses TSH and blocks thyroid hormone activation. This creates daily or meal-to-meal variability—e.g., post-meal crashes worsening hypothyroid symptoms.

Positive Dietary Changes (e.g., Elimination Diets): Switching to an anti-inflammatory diet (gluten-free, dairy-free, Paleo, or AIP) often leads to long-term stability, but the transition can cause temporary fluctuations. Removing triggers reduces inflammation over time, but initial "die-off" (from shifting microbiome) or detox reactions can mimic worsening symptoms for days to weeks. Conversely, reintroducing a trigger during testing can confirm its role by reproducing symptoms.

Microbiome Shifts: Diet alters gut bacteria rapidly (within 24–48 hours). A poor diet promotes dysbiosis, reducing T3 conversion in the gut and increasing LPS (bacterial toxins) that fuel autoimmunity.

How fluctuations happen: Eating a trigger food (e.g., pizza with gluten and dairy) can increase gut permeability ("leaky gut") within hours, allowing undigested proteins into the bloodstream. This sparks inflammation, raises cytokines, and temporarily impairs T4-to-T3 conversion or boosts reverse T3. Symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, or joint pain may worsen for 1–3 days (or longer with repeated exposure).

Infections and Fluctuations

Infections—acute, chronic, or reactivating—powerfully trigger thyroid flares by activating the immune system and often through molecular mimicry, where pathogen proteins resemble thyroid proteins, leading to cross-reactivity.

Viral Infections: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, cause of mono) links strongly to Hashimoto's. Many patients trace symptom onset to a past EBV infection; the virus can linger dormant and reactivate under stress, directly infecting thyroid cells or triggering antibodies.

Other viruses like CMV, HSV, or even recent ones (e.g., post-COVID thyroid issues reported) can do the same. Reactivation causes intermittent immune activation.

Bacterial and Gut Infections: Pathogens like H. pylori, Yersinia enterocolitica, or Borrelia (Lyme) use molecular mimicry. Gut-focused infections (SIBO, parasites, or dysbiosis from antibiotics) impair thyroid medication absorption and T3 conversion while leaking toxins that drive systemic inflammation.How fluctuations happen: An acute infection (flu, sinusitis) can spike inflammation broadly; chronic gut infections cause ongoing variability tied to digestion or die-off during treatment.

How fluctuations happen: During a flare (e.g., from stress or another illness), rising viral antibodies cross-react with thyroid tissue, causing inflammation and erratic hormone release. Symptoms may intensify for weeks, then subside until the next trigger.

From a functional medicine viewpoint, these triggers disrupt the delicate balance of the immune system, gut, hormone conversion, and inflammation—leading to episodic "flares" rather than constant issues.

These triggers are inherently episodic—a single triggering meal or a stress-induced viral reactivation can shift symptoms noticeably, explaining the "good days and bad days" pattern.

Functional approach: Test for chronic infections (EBV/EBNA/VCA antibodies, stool tests for pathogens, or organic acids urine test).

Support with antimicrobials (herbs like oregano oil, berberine under guidance), immune modulation, and addressing triggers to prevent recurrences.

Diet and infections often interplay (e.g., poor diet weakens immunity, increasing infection risk). Many patients see more consistent symptoms once these are addressed.

Links to autoimmunity: Low bacterial diversity is common in Hashimoto's; certain pathogens trigger molecular mimicry.

Functional approach: Comprehensive stool testing (e.g., GI-MAP). Heal with probiotics, prebiotics, L-glutamine, bone broth, and eliminating triggers (gluten, dairy often cross-react).

5. Nutrient Deficiencies and Toxin Exposure

Thyroid function relies on specific nutrients for hormone synthesis, conversion, and protection, while toxins disrupt these processes.

Key nutrients:

Selenium protects thyroid from oxidative damage and supports deiodinases.

Iron/ferritin for thyroid peroxidase enzyme.

Zinc for T3 receptor function.

Vitamin D modulates immunity.

Deficiencies fluctuate with diet, absorption issues, or increased needs during stress.

Toxins: Heavy metals (mercury), mold mycotoxins, BPA/plastics, or halides (fluoride) compete with iodine or burden liver detox, causing variable interference.

Why fluctuating: Seasonal diet changes, exposure variations (e.g., mold in damp weather), or poor gut absorption lead to ups and downs.

Root Cause approach: Comprehensive nutrient testing (serum + intracellular if possible). Replete gradually (e.g., Brazil nuts for selenium). Detox support with sauna, binders (charcoal, clay), and liver herbs (milk thistle).

6. Hormonal Interplay (Sex Hormones, Blood Sugar)

Thyroid hormones interact with estrogen, progesterone, insulin, and cortisol.

Sex hormones: Estrogen (higher in luteal phase or perimenopause) increases thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), binding more T4/T3 and reducing free (active) levels. Progesterone supports thyroid utilization.

Blood sugar: Insulin resistance or hypoglycemia triggers cortisol release, impairing conversion. Meals high in refined carbs cause swings.

Why fluctuating: Cyclical (menstrual cycle, perimenopause) or meal-related changes drive daily/weekly shifts—e.g., worse fatigue mid-cycle or post-meal crashes.

Functional approach: Test sex hormones (Dutch test for metabolites), stabilize blood sugar (low-glycemic diet, chromium, berberine). Balance estrogen with DIM/broccoli sprouts or progesterone support if needed.

These interconnections explain why symptoms feel like a moving target. Addressing multiple layers often brings more stability than medication adjustments alone. Tracking patterns in a journal can reveal your personal triggers.

Schedule a call with me to get to your root cause and start feeling well again.