Managing Glycemic Load: A Comprehensive Guide to Sweetener Choices and Health

In today’s food landscape, sweeteners are ubiquitous, shaping our diets and impacting our health in profound ways. From processed snacks to beverages, added sugars contribute significantly to glycemic load, affecting blood sugar regulation, gut health, and overall well-being. Understanding how to manage glycemic load and make informed sweetener choices is crucial for maintaining metabolic health, supporting digestive function, and reducing the risk of chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes. This blog post explores the types of sweeteners, their effects on the body, and practical strategies for reducing reliance on added sugars, with a focus on bio-individuality and long-term health.

Why Glycemic Load Matters

Glycemic load (GL) measures how a food affects blood sugar, factoring in both its glycemic index (GI) and the amount of carbohydrates in a serving (GL = GI × grams of carbohydrates ÷ 100). High glycemic load foods cause rapid blood sugar spikes, which can strain metabolic processes, promote insulin resistance, and exacerbate digestive issues, particularly in individuals with conditions like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or candida overgrowth. Managing glycemic load is especially important for those with gluten-related disorders, as inflammation and gut dysbiosis often amplify metabolic challenges.

Reducing added sweeteners is a key strategy for lowering glycemic load. This not only stabilizes blood sugar but also supports the gut microbiome, reduces inflammation, and curbs cravings for hyper-palatable foods. Let’s dive into practical guidelines for managing sweetener intake and explore the science behind different sweetener types.

Guidelines for Reducing Sweetener Use

Reducing Added Sweeteners

The first step in managing glycemic load is minimizing reliance on added sweeteners. Here are actionable strategies:

Eliminate Unnecessary Sweeteners: Identify foods and beverages with added sugars (e.g., sodas, packaged snacks) and opt for unsweetened versions. For example, choose plain yogurt over flavored varieties and sweeten naturally with fresh fruit.

Uncover Hidden Sugars: Processed foods often contain hidden sugars under names like corn syrup, dextrose, or maltose. Reading ingredient labels helps identify these sources, allowing you to choose healthier alternatives, such as homemade versions with reduced sugar content.

Prioritize Whole Foods: Fresh fruits like berries or apples provide natural sweetness with fiber, vitamins, and minerals, reducing glycemic impact compared to refined sugars.

Use Natural Sweeteners Sparingly: Honey, maple syrup, and molasses offer trace nutrients and have been part of human diets for millennia. Use them in moderation to balance flavor and health benefits.

Recalibrating the Palate

Many people are accustomed to overly sweet foods due to the prevalence of hyper-palatable processed products. Gradually reducing sweetener use can reset taste preferences:

Incremental Reduction: Dilute sugary drinks with water or reduce sugar in recipes by 10–25% over time. For instance, cutting sugar in banana bread recipes often goes unnoticed while lowering glycemic load.

Patience Pays Off: Taste buds adapt within weeks, making less sweet foods more enjoyable and reducing cravings for intense sweetness.

Expanding Flavor Profiles

Diversifying taste experiences can reduce reliance on sweetness:

Explore Other Tastes: Incorporate sour (e.g., lemon juice), bitter (e.g., arugula), or umami (e.g., mushrooms, broth) flavors to enrich meals. Try sipping warm broth before dessert or eating a sour pickle during a sugar craving to shift taste perception.

Enhance Culinary Variety: Experimenting with herbs, spices, and savory ingredients creates satisfying dishes without relying on sugar.

Approaching Novel Sweeteners with Caution

Novel sweeteners, such as sugar alcohols or artificial substitutes, are often marketed as healthy alternatives, but their long-term effects are not fully understood:

Moderation is Key: Many alternative sweeteners lack extensive research on their impact on hormonal signaling, metabolism, and the gut microbiome.

Bio-Individuality Matters: Responses to sweeteners vary. Monitor symptoms like bloating, cravings, or metabolic changes to assess personal tolerance.

Types of Sweeteners and Their Impacts

Understanding the properties of different sweeteners helps in making informed choices. Below, we categorize sweeteners and explore their glycemic and health effects.

Caloric Sweeteners

Caloric sweeteners provide energy and include natural sugars like:

Sucrose (Table Sugar): A disaccharide of glucose and fructose (GI: 65), commonly found in processed foods.

Fructose: A monosaccharide in fruits, honey, and vegetables (GI: 25). While it has a low GI, its metabolism is complex (see below).

Other Natural Sugars: Honey, maple syrup, molasses, coconut sugar, agave nectar, corn syrup, and rice syrup contain varying ratios of glucose, fructose, and trace nutrients. Their glycemic impact depends on serving size.

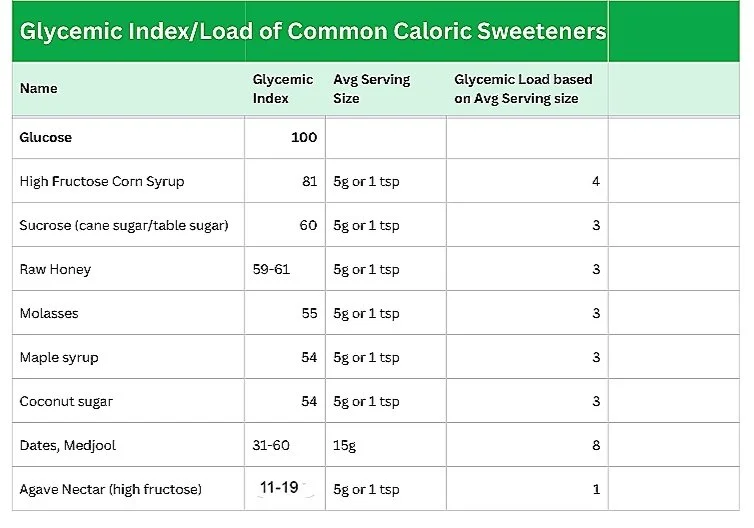

Glycemic Index/Load of Common Caloric Sweeteners

Serving size significantly affects glycemic load. For example, a 16 oz can of Coca-Cola contains 52g of high fructose corn syrup, far exceeding the 5g serving size used in GL calculations, leading to substantial blood sugar spikes despite its low GL rating.

Natural Non-Caloric Sweeteners

These plant-based sweeteners provide intense sweetness without calories:

Stevia: Derived from Stevia rebaudiana, stevia’s steviol glycosides are 200–400 times sweeter than sugar (GI/GL: 0). Whole leaf stevia offers antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties (Papaefthimiou et al., 2023). Studies suggest stevia has minimal impact on insulin and may improve pancreatic beta cell function in type 2 diabetics.

Monk Fruit Extract (Luo Han Guo): Contains mogrosides, providing calorie-free sweetness (GI/GL: 0). Note that many stevia and monk fruit products include sugar alcohols like erythritol as the primary ingredient.

While these sweeteners don’t raise blood glucose, they may influence appetite-regulating hormones in some individuals, though evidence suggests minimal impact.

Sugar Alcohols (Polyols)

Sugar alcohols, such as xylitol, erythritol, and sorbitol, are carbohydrates with a lower glycemic impact due to partial absorption:

Xylitol: Slightly increases glucose and insulin but is effective in reducing cavities when used in gums or mouthwashes.

Erythritol: Highly absorbed and excreted in urine, causing fewer digestive issues (tolerance: ~0.66 g/kg/day for men, 0.80 g/kg/day for women; Mazi & Stanhope, 2023). It may induce satiety hormones like cholecystokinin.

Sorbitol: More likely to cause digestive upset due to poor absorption.

Glycemic Index/Load of Common Sugar Alcohols

Sugar alcohols act as prebiotics, potentially increasing beneficial bacteria like bifidobacteria, but excessive intake can cause bloating, diarrhea, or gas, especially in IBS/IBD patients. One study linked erythritol to increased gut inflammation in mice models of IBD (Jiang et al., 2023).

Inulin

Inulin, a prebiotic fructan, contains non-absorbable calories and has no glycemic impact. Found in chicory root, onions, bananas, and asparagus, it supports gut health by promoting beneficial bacteria and may improve glycemic control and lipid profiles in type 2 diabetics (Dehghan, 2012). It’s used in low-sugar products and probiotic supplements.

Artificial Non-Caloric Sweeteners

Synthetic sweeteners like aspartame, sucralose, saccharin, and acesulfame potassium provide intense sweetness without calories but pose health risks:

Health Concerns: Research links artificial sweeteners to impaired glycemic responses, glucose intolerance, and reduced gut barrier function (Shil et al., 2020). Aspartame is a potential carcinogen, and some studies suggest pathogenic microbiome changes (Ruiz-Ojeda et al., 2019).

Recommendation: Avoid artificial sweeteners due to their potential metabolic and gut health impacts.

Special Considerations

Hormonal and Satiety Effects

Sweeteners influence hormones like insulin, cholecystokinin, and glucagon-like peptide-1, which regulate blood sugar and satiety:

Erythritol and Xylitol: Promote satiety by slowing gastric emptying, aiding glycemic control.

Stevia: May improve insulin sensitivity without significant insulin spikes.

Low Insulin Response: While beneficial for reducing insulin resistance, low insulin can reduce leptin release, potentially increasing appetite and caloric intake.

Digestive Health

Sugar alcohols, particularly sorbitol and xylitol, can cause digestive upset due to fermentation in the gut. Erythritol is better tolerated, but IBS/IBD patients may be more sensitive. Inulin supports gut health, while artificial sweeteners may disrupt the microbiome.

GMOs and Consumer Preferences

Most erythritol is derived from GMO cornstarch, which may not align with preferences for non-GMO foods. Always check labels for transparency.

Understanding Fructose

Fructose, with a GI of 25, is often considered a low-GI sweetener, but its metabolism presents unique challenges:

Liver Metabolism: Unlike glucose, which is used by all cells, fructose is metabolized by the liver, where high doses can promote insulin resistance, triglyceride production, and uric acid buildup, linked to hypertension, kidney stones, and gout (Gugliucci, 2017; Sigala et al., 2021).

Appetite Regulation: Fructose stimulates less insulin and leptin than glucose, potentially increasing appetite and contributing to metabolic syndrome.

Fruit vs. Processed Fructose: Whole fruits have low fructose content (e.g., 8–10g in an apple) and fiber, minimizing glycemic impact. In contrast, a 16 oz glass of grape juice contains 37.2g of free fructose, causing rapid absorption and metabolic strain.

Insert chart here: Common Names for Refined Sugar in Ingredient Labels

Other names for refined sugar

Allulose, a rare sugar derived from fructose, shows promise for improving glucose tolerance but requires further research. It’s approved in the U.S. but not in the EU or Canada.

Practical Tips for Selecting Sweeteners

Read Labels Carefully: Products labeled “stevia” or “monk fruit” often contain sugar alcohols like erythritol. Check ingredient lists for accuracy.

Mix Sweeteners: Combine caloric (e.g., honey) and non-caloric (e.g., stevia) sweeteners to balance flavor, glycemic load, and satiety. For example, halve the honey in a recipe and add a pinch of stevia.

Monitor Bio-Individuality: Track symptoms like bloating, cravings, or metabolic changes after consuming sweeteners. Some individuals report that alternative sweeteners hinder weight loss or perpetuate cravings.

Contextualize Health Claims: A sweetener’s benefits depend on what it replaces. For type 2 diabetics, stevia may reduce cardiometabolic risks compared to fructose, but it’s not inherently health-promoting for all.

Integrating Sweetener Management with Digestive Health

Reducing glycemic load supports digestive health, particularly for those with gluten sensitivities, SIBO, or candida overgrowth, as high-sugar diets exacerbate dysbiosis. A low-sugar, whole-food-based diet, combined with prebiotics like inulin, can restore gut balance. For example, incorporating unsweetened yogurt with fruit and a sprinkle of inulin can nourish beneficial bacteria while keeping glycemic load low.

Practitioners can create resources like handouts listing hidden sugars and low-GI alternatives to guide clients. Personalized dietary reviews help identify high-sugar foods and suggest substitutions, enhancing compliance and outcomes.

Conclusion

Managing glycemic load through informed sweetener choices is a powerful tool for optimizing metabolic and digestive health. By reducing added sugars, prioritizing whole foods, and cautiously incorporating natural non-caloric sweeteners or sugar alcohols, individuals can stabilize blood sugar, support gut health, and reduce inflammation. Bio-individuality and context are key—monitor personal responses and consult practitioners for tailored guidance. With these strategies, you can enjoy sweetness in moderation while fostering long-term wellness.